Brian Kaminski, RBT, Graduate Student of Behavior Analysis

It’s January in the state of Michigan, which means daylight past 5 pm and temperatures in the double digits are a distant memory of seasons past.

As such, more than a fair share of my recent evenings have been spent bundled up indoors, safe from the elements, and cozied up with my Netflix queue geared and ready.

(I’ve conceded that my vow to cut back on screen-time will resume once the windchill gets back above -3 ° and I can feel my face again outdoors).

My most recent binge has been on the critically acclaimed series Mad Men, a period drama which follows the lives of prominent advertising executives on Madison Avenue in the 1960s.

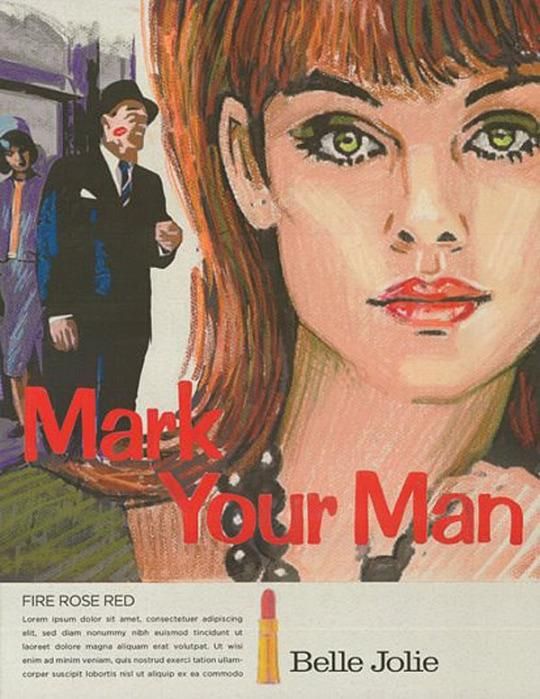

My favorite aspect of the series has been watching the evolving creative processes behind each “big pitch” – whether that be for lipstick …

Popsicles …

… or Lucky Stripe tobacco.

Let’s explore what made these advertising campaigns so effective, as well as other marketing strategies you encounter on a daily basis through the lens of applied behavior analysis.

“Reinforcer Effectiveness”

When it comes to advertising, we are essentially in the business of selling reinforcers – goods or services that look to evoke consumer behavior.

In a marketplace that is flooded with products, companies must demonstrate their superiority over competitors.

In other words, the “superior product” = “most effective reinforcer.”

ABA has a long line of empirical research examining the factors which determine the reinforcing effectiveness of a stimulus – among them, size, immediacy, quality, and motivating operations (Cooper et. al, 2007).

Size

The larger the magnitude of a reinforcer, the greater its reinforcing effect.

Super Size, anyone?

Immediacy

The more immediate the reinforcer, the greater its reinforcing effect.

Sorry Sprint, T-Mobile has you here.

Quality

The greater the quality of reinforcement, the greater its reinforcing effect.

Because no one has time for ads.

Motivating Operation

The greater the “momentary value” of a reinforcer, the greater its reinforcing effect.

Let’s explore this one a bit further.

“Motivating Operations”

In addition to the “effectiveness” of a given reinforcer, there are environmental variables which alter the reinforcer’s momentary value. These “value-altering” variables are known as motivating operations (MO).

In other words, MO’s alters what an individual “wants” at a given moment.

Motivating operations can alter the value of a reinforcer in both directions.

A motivating operation which decreases the value of a reinforcer is called an abolishing operation (AO). Eating an entire box of Krispy Kreme donuts reduces the effectiveness of food as a reinforcer (this “satiated” state is an “abolishing operation” ).

A motivating operation which increases the value of a reinforcer is called an establishing operation (EO). Hunger increases the effectiveness of food as a reinforcer (“Pass me those Krispy Kremes, please!”).

In most cases, advertisers are working to conjure up an “EO” in a consumer, increasing the reinforcing value of their product.

Conditioned Motivation Operations

Some motivating operations are unlearned, or “unconditioned” – meaning they are intrinsic to every individual. Hunger, thirst, sleep deprivation, extreme temperatures, & pain are all examples of unconditioned motivating operations (UMO).

Other motivating operations which are the result of an individual’s learning history are called conditioned motivating operations (CMO).

For example, a sun burn would suddenly make aloe vera a more valuable reinforcer.

Seeing your gaslight on “E” suddenly increases the value of a quarter-tank of gas.

Taking a tumble off a ladder while painting suddenly makes short-term disability insurance a hotter commodity.

Whatever the case, it is important to remember that the value of a reinforcer is constantly in flux. It’s an advertiser’s goal to capitalize on this variability and “push the needle” in the direction of their product.

A month from now, approximately 100 million viewers will be tuning in for the advertising event of the year – the Super Bowl.

This year, in between the Doritos and Budweiser commercials, be on the lookout for the behavioral principles driving each ad – it may be more entertaining than the game itself.

Then score one more for behavior analysis.

References

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied Behavior Analysis (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.