Brian Kaminski

The holiday season is officially upon us. Sounds of Bing Crosby have filled the airwaves, neighborhoods are aglow with LED and twinkle lights, while businesses begin to embrace for one of their biggest paydays of the year – Black Friday.

We’ve all seen photos or perhaps experienced firsthand the mobs of shoppers that stampede through retailers in search of unbeatable savings. Some people even taking extreme measures of camping overnight, for days, even weeks, to secure the year’s hottest items.

What can behavior analysis teach us about this frenzied, even irrational, consumer behavior? Well, it turns out quite a bit.

Behavioral Economics

When it comes to matters of “consumption,” (post-Turkey day shopping or otherwise) behavioral economics offers rich insight within a behavioral framework.

Behavioral economics, as defined in behavior analytic terms, examines the relationship between environmental constraints and its effects on reinforcement.

This wing of behavior analysis explores how manipulations of varying dimensions of reinforcement (quality, effort, delay, density, etc.) can impact behavior.

With the help of some examples, we’ll explore a few behavioral economic principles and see how it relates to our crazed holiday shopping habits.

Concept #1 – Delay Discounting

When it comes to Black Friday shopping, one behavioral economic principle on full display is “delay discounting.”

Delay discounting refers to the decline in value of a reward (reinforcement) as delay in delivery increases.

Put in everyday terms, this principle relates to our ability to “delay gratification.”

A popularized study which illustrates this concept is the “Stanford Marshmallow Experiment” conducted in the 60’s and 70’s. In this study, psychologist Walter Mischel would offer a child a choice between one small reward provided immediately (a marshmallow or other small edible) or two small rewards if they waited a short period of time.

While many inferences have been drawn from the results of this study into the relationship between “life success” and delayed gratification, the underlying conclusion was the individual tendency of favoring “smaller sooner” rewards over “larger later” rewards.

When it comes to Black Friday, shoppers have to ask themselves the same question. Do I really want to buy the Apple Watch Series 3 when a superior Series 4 will come out in a few months? When it comes to such commodities, sometimes the most desirable is the one you have in your hands.

Takeaway #1 – “We want it, and we want it now!”

Concept #2 – Open v. Closed Economies

One of the most basic concepts at the heart of economics is the principle of “supply and demand.” When supplies are scarce, demand increases; when supplies are abundant, demand decreases.

The same concept holds true in the behavioral realm. In the “economy” of behavior interventions, the value of a reinforcer depends on its availability inside and outside its “system.”

When reinforcement is only available within a target system (context or setting), it is considered a “closed economy.” In a therapy setting where items are only delivered following a child’s vocal request, the student is operating within a closed economy.

“Open economies” are those in which additional access to the reinforcer is available outside the target system. Using the same example, a child would be in an “open economy” if items were delivered through additional means (vocal approximations, PECS, sign language, etc.).

Reed, Niileksela, and Kaplan (2013) describe the interplay between economy systems and supply and demand as follows:

As the notion of supply and demand suggests, supplemental access to the reinforcer outside the target system increases its supply and subsequently decreases its demand. In classroom settings where extra credit points are abundantly available (open economies), assignment completion may be low because there is plenty of opportunity to access class points outside of the bounds of the in-class assignments and homework. In a classroom where there is no extra credit available (closed economies), assignment completion may be high because the students must work within the bounds of the in-class assignments and homework to earn their points.

While all of our shopping this Friday will be done within an open economic system, the same premise of supply and demand applies.

“Best Buy is only selling ten 60″ Ultra HDTVs tomorrow?! We better go early to get a spot in line!”

Takeaway #2: “Buy now while supplies last!”

Concept #3 – Demand Functions

This Friday, retailers hope to lure potential shoppers with promises of unbeatable savings. The critical decision they are faced with is just how low to set a particular price point to maximize consumer engagement and profit margin.

Behavior analysts must ask themselves the same question when setting the “price” of a reinforcer for a learner. They must seek to identify the highest level of responding required before problem behavior or “ratio strain” is exhibited.

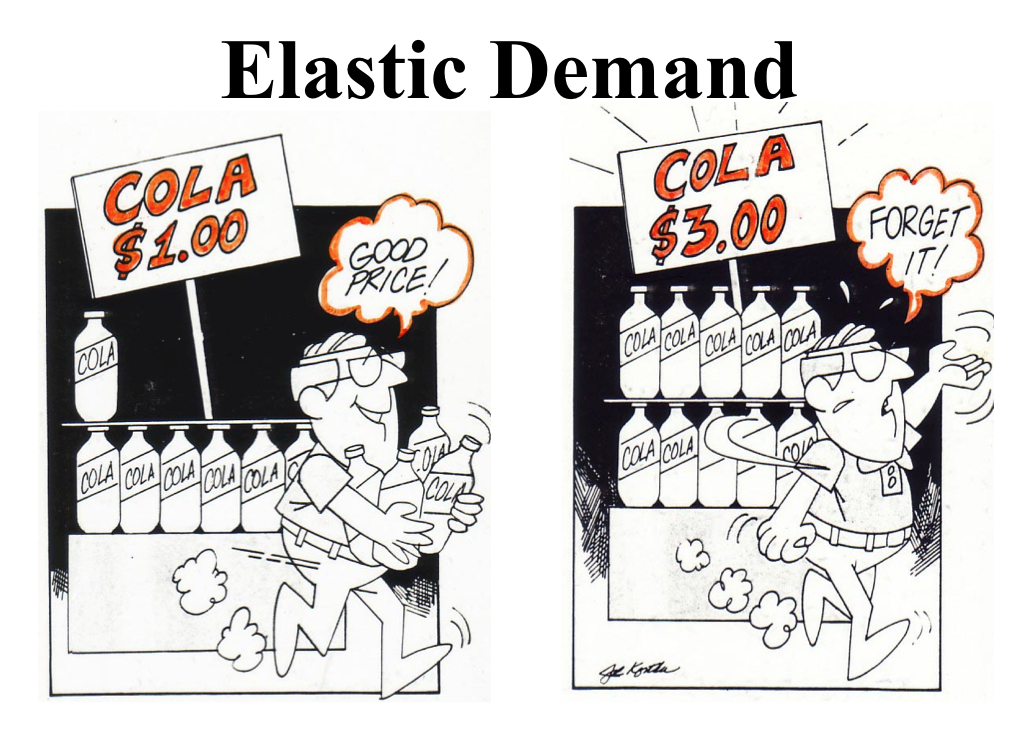

The extent to which consumption remains stable across increases in price is considered the consumer’s “demand.”

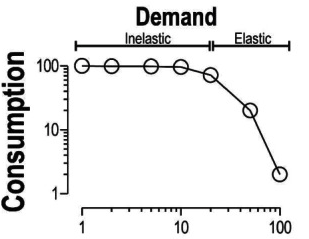

Demand is “inelastic” when consumption is relatively stable across increases in unit price.

Demand becomes “elastic” at the point in which increases in unit price yields a decrease in consumption (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Depiction of consumption as a function of price (a demand function). Consumption remains constant (“inelastic”) until a unit price of 20; consumption decreases at a unit price above 20 (“elastic”). This figure is from “Behavioral Economics: A Tutorial for Behavior Analysts in Practice” published in Behavior Analysts in Practice (Reed, Niileksela, & Kaplan, 2013).

A fun aside – behavioral economists have coined the term “breakpoint” for the unit price at which zero reinforcers are consumed (responding has ceased).

As evident by our first thousand dollar smartphone with the iPhone X, businesses are still clearly pushing the envelope to test our breaking point for our favorite gadgets.

Takeaway #3 – What’s your breaking point?

For practitioners of ABA, an understanding of behavioral economic principles can help you design interventions with optimal efficacy, allowing you to get the most “bang for your buck” with each client you serve.

As Black Friday deals come to a close this year, perhaps you’ll even have a little more insight into your own shopping behavior …

Right in time for Cyber Monday.

References

Reed, D. D., Niileksela, C. R., & Kaplan, B. A. (2013). Behavioral Economics: A Tutorial for Behavior Analysts in Practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice,6(1), 34-54. doi: 10.1007/BF03391790

To learn more about Behavioral Economics, I highly recommend listening to Dr. Derek Reed, BCBA-D, on “The Behavioral Observations Podcast with Matt Cicoria.” (Click here).

Dr. Reed also provides a list of helpful resources for researchers and clinicians from the University of Kansas Applied Behavioral Economics Lab that you can visit here .