Brian Kaminski, RBT, Graduate Student of Behavior Analysis

Behavior analysts are engineers of “the good life.”

If there was one universal goal in every treatment plan ever conceived, it would be this: implementing measures to improve & enrich our clients’ quality of life.

Whether that be achieved through teaching communication skills to a child with developmental disabilities or designing organizational systems to increase workplace satisfaction, behavior analysts are constantly looking for ways to promote lives of richness and vitality in those they serve.

It is perhaps due to this concern over cultivating full and meaningful lives that I was particularly disturbed when presented with some consumer statistics in a recent TED Talk.

The presenter, Adam Alter of New York University’s Stern School of Business, was commenting on the effects of increased “screen time” over the past decade on reported measures of happiness.

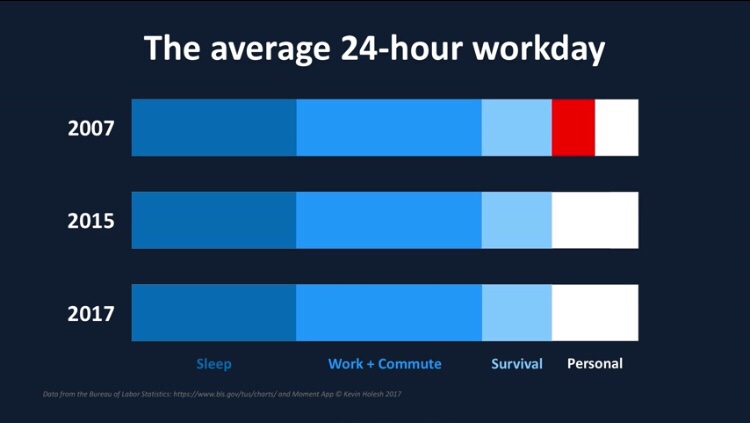

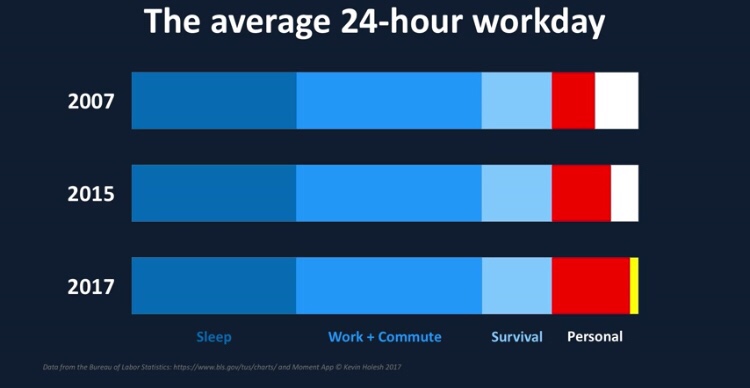

The graph presented by Alter, comprised of data reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, displayed the proportion of time devoted to various tasks over an average 24-hour workday from 2007 through 2017.

The white space represents “personal time” – time spent on recreation and leisure instead of the “survival tasks” of eating, bathing, etc.

Watch what happens to this white space in 2007, the release year of the first iPhone (screen time denoted in red).

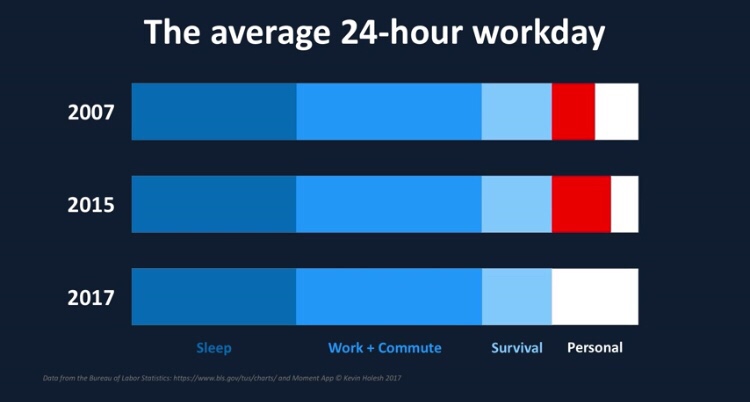

Eight years later:

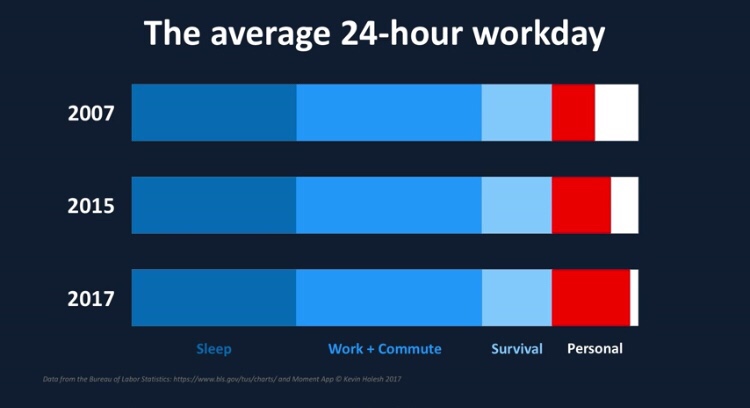

And in 2017:

To illustrate the remaining personal time not occupied by screens (yellow), Alter adds,

“This yellow area … is where the magic happens. That’s where your humanity lives, and right now its in a very small box.”

As alarming as this trend appears, I am not attempting to decry the use of these technologies altogether or present the issue as some sort of moral dilemma.

Rather, my concern is that individuals are losing out on other meaningful forms of reinforcement outside of their tech bubbles.

Furthermore, as someone who spends a considerable portion of their professional life teaching social skills to adolescents, I cannot help but consider the social ramifications on younger generations who communicate largely through 140-characters or less, retweets, and emojis.

Hmmm … seems like we have a problem of social significance on our hands.

Not to fear – Behavior Analysis to the rescue!

I now present you with five behavioral strategies to reduce screen time so you can go on living the good life.

1. Establish Baseline

Perhaps the data reported by Alter has you saying,

“Yeah, I probably could cut back on screen time a bit myself.”

If so, it would not be enough to say you want to use your phone or tablet “less.”

“Less” than what?

You first would have to establish your baseline rate of use – your current level of behavior prior to any sort of intervention.

The difficulty with recording baseline for screen time is that most of us use our devices so frequently and sporadically – manually recording our usage history with accuracy would be almost impossible.

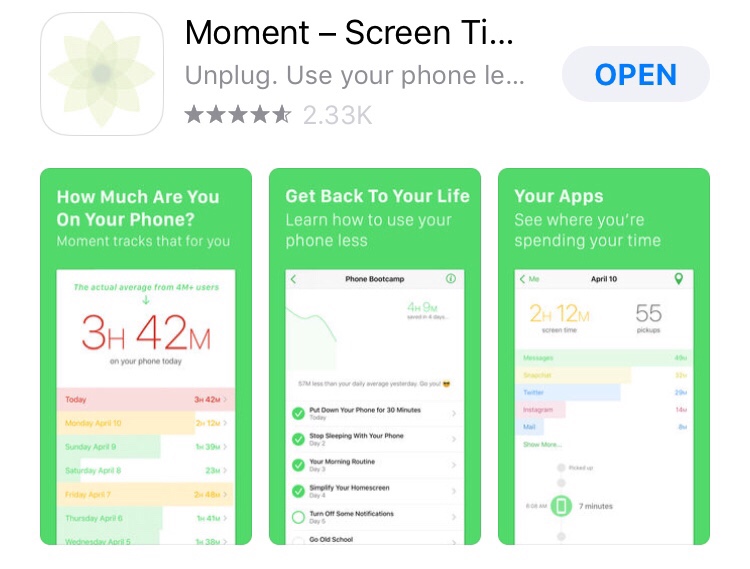

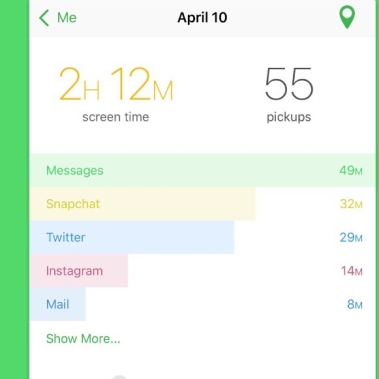

Thankfully, the “Moment” app (FREE on iOs) makes tracking screen time easier than ever.

The app runs seamlessly in the background and provides you with sophisticated screen time breakdowns.

Once you collect baseline data for a typical week, you are ready to start goal setting.

2. Incorporate a Performance Manager

Like any behavior change endeavor, the support of a community with similar values and goals makes overcoming setbacks more achievable.

A good Performance Manager will also keep you accountable – someone who helps monitor your progress and deliver consequences for meeting or failing to meet goals.

Another cool feature of the “Moment” app is the “My Family” mode, which allows you to compare screen time usage among family members and serve as one another’s Performance Manager.

Try to make the exercise fun and engaging!

Set personal or family goals.

Establish positive consequences that everyone has the opportunity to achieve (e.g. “If we all use our phone less than 5 hours each this week, we’ll go out to dinner on Saturday.”).

Consider making it a competition – sometimes the most powerful reinforcer is bragging rights.

3. Eliminate the “SD’s”

Checking my email soon turned into an unceasing game of Whack-A-Mole that I couldn’t resist.

The moment I received an email, I was clicking and responding as quickly as possible to get rid of the pesky notification alert.

In behavior analysis, we would say that my notifications were functioning as a discriminative stimulus (SD), “a stimulus in which a particular response will be reinforced …” (Malott, 2013).

In this case, the SD (notification), caused a response (clicking) because when that stimulus was present in the past, clicking produced a reinforcer (elimination of email from inbox).

It was years later when I came up with a groundbreaking solution – turning my notifications off (*gasp*).

In turn, this eliminated the SD’s for my click-happy behavior and dramatically reduced the time I spent on my phone.

This might seem like a radical suggestion in our current FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) culture, but I found that messages of importance were still being responded to promptly, while trivial messages were simply ignored.

Consider setting a rule: “I’ll check my email once daily at noon.”

I found that shockingly, I survived quite well without pausing to delete Eddie Bauer and Spotify ads every two hours – I think you will likely have the same experience.

4. Increase the Response Effort

Another simple way to reduce screen time is by increasing the response effort to access nonessential, time-zapping apps.

Consider deleting app shortcuts off your home-screen to force yourself to manually log in every time you want to view that meme on Twitter.

That extra required effort and momentary pause might be just the break you need to choose another activity.

5. Identify Replacement Behaviors

So let’s say you’ve completely bought into the notion that you need to reboot your screen viewing habits.

You successfully implement Steps 1-4 and have succeeded at reducing your screen time.

Now what?

It might be helpful to have some replacement behaviors identified beforehand so you know what to do with yourself.

Haven’t read a good book in a while? Stop by the library after work.

Have eaten nothing but takeout lately? Find a good recipe and make sure your refrigerator is fully stocked.

For a few months after graduating undergrad, I lived in a house with maddeningly spotty wifi. I found things to do away from a screen because I was forced to.

I took up wood engraving.

While I can’t claim that any of the results were “good” (a lot of relatives got some pretty amateur looking wall accessories that year), I found a new craft that I enjoyed learning. This wasn’t something I could find in my Netflix queue.

Having a similar activity in mind (“Pinterest Fail” or otherwise) before you ditch your old screen-viewing ways will prevent you from lapsing back into old habits.

I would like to finish by sharing Alter’s talk – I think you will find his comments insightful and even motivating enough to change your own screen viewing behavior.

Then get up, go for a walk, find a good book, and give your mother a call.